In the Fireside Science series – SciFund Challenge’s Guide to Life, the Universe and Everything!

This is an edited version of a post in my blog – chromosomesandcancer.com. The back-story is that I was approached by a national current affairs program to do an interview on telomeres. Being a cancer researcher I thought the story might be about cancer. It turned out the focus was on cosmetics. How so? Having done some extra background reading I’ve tried to put together a balanced view of telomeres’ role in cancer and ageing.

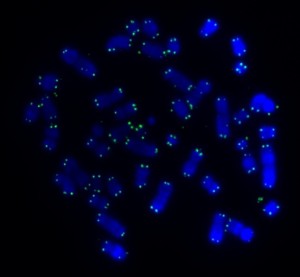

Our cells have 46 long strings of genes. When a cell finishes growing and divides to become two cells, these 46 strings of genes fold up to become recognizable chromosomes – we can see these with a microscope.

At each end of a chromosome there’s a short stretch of DNA called the telomere that caps the chromosome to protect it from eroding or from sticking to other chromosomes. If two chromosomes stick together, they become one abnormal chromosome. Abnormal chromosomes like this can be a cancer risk.

Click here for a telomere fusion animation.

Our telomeres start out at a set length in a fertilized egg. A tiny part of the telomere is lost every time a cell divides, so our telomeres get shorter as we grow older. Other factors, such as extreme psychological stress, and toxins such as chemotherapy, are also thought to cause telomere shortening.

It seems likely that short telomeres can cause diseases that we associate with ageing, such as cancer, osteoarthritis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Some people are born with short telomeres – and can get a similar range of diseases, symptomatic of premature ageing.

Here’s the paradox – short telomeres are a cancer risk, but established cancers are able to make longer telomeres so that they can divide indefinitely and become immortal.

It’s been suggested that shortening the telomeres of cancer could be an effective treatment. Some researchers are trying to do this by destroying an enzyme (a protein which causes chemical reactions) called telomerase, which lengthens telomeres.

It’s also been suggested that if we could lengthen our telomeres we could cure the diseases associated with short telomeres, or cancel the effects of ageing. So some other researchers are looking at the possibility of using telomerase to reverse the effects of ageing. Some cosmetics containing a chemical that’s been reported to activate telomerase (TA-65®) are already available. This same chemical is being tested for use as a treatment for diseases linked to ageing and short telomeres.

These potential treatments will need extensive testing to see if they work, but also to make sure they don’t have unwanted side effects. Cells with critically shortened telomeres and chromosomes that are joined together usually self-destruct. But by re-lengthening the telomeres, cancer cells can override the self-destruction mechanisms. So does lengthening telomeres to reverse ageing increase the risk of cancer? There’s debate about this, but obviously it would need to be pretty clear that the risk is negligible before telomere lengthening drugs are used as an anti-ageing strategy. TA-65® is allowed in cosmetics because they aren’t governed by the same regulations as drugs.

There’s a strong link between stress-related diseases and short telomeres. There’s evidence that drug-free measures like reducing stress, exercise and an improved diet, may stop or even reverse premature telomere shortening. These are safe and available now.

Telomeres were originally a niche specialty area of basic science with no obvious health implications. Telomere research now gives some hope to people with cancer and other diseases, and even to people who are hoping to find the key to eternal youth.

FURTHER READING (OPEN ACCESS)

C. Buseman 2012. Is telomerase a viable target in cancer? Mutation Research 730:90-97

E. Callaway 2010. Telomerase reverses ageing process. Dramatic rejuvenation of prematurely aged mice hints at potential therapy. Nature 28th November 2010 (published online).

B. de Jesus et al. 2011. Aging by telomere loss can be reversed. Cell Stem Cell 8:3

C. Harley et al. 2011. A natural product telomerase activator as part of a health maintenance program. Rejuvenation Research 14:45-56.

R. MacKinnon and L. Campbell 2011. The role of dicentric chromosome formation and secondary centromere deletion in the evolution of myeloid malignancy. Genetics Research International Article ID 643628

T. Morin. http://www.dayspamagazine.com/article/spa-products-tale-telomeres A balanced article on telomeres in Dayspa Magazine online.

OTHER REFERENCES

E. Blackburn and E. Epel 2012. Too toxic to ignore. Nature 490:169-171 (about stress, disease and telomere shortening). Note, Elizabeth Blackburn is Australia’s only female Nobel Prize winner (in science at least) – she shared the prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2009 for her discovery of telomeres.

B. de Jesus et al. 2013. Telomerase at the intersection of cancer and aging. Trends in Genetics (available online 19th July 2013)