#SciFund Challenge Class

Part 2: The Real Purpose of Your Academic Poster

What's the point of presenting an academic poster anyway? You may think that the primary purpose is to present information to your peers at a conference or other academic gathering - but you would be incorrect.

To understand what the primary purpose actually is, let's take a step back. Why would a scientist such as yourself go to a conference in the first place? What would you hope to get out of it? Maybe you are looking for a postdoc. Maybe you are looking to convince your colleagues to use a method that you have devised. The potential things you could get out of a conference are limitless (more on this later), but almost all of the most important things will: 1) advance your career in some way and 2) involve connecting with some of your colleagues.

Think about it. Pretty much anything that you are trying to achieve at a conference (or other academic gathering) involves talking to other folks. For example, if you're trying to get people in your field to use your method, the first step is to engage them in conversation about your method. If you're trying to get a postdoc or other academic position, it's essential to talk to people who might be in a position to hire you.

As a consequence, if having conversations with the right people is the key to conference success (which it is), then the primary purpose of your academic poster must be to encourage those conversations. Don't get us wrong, it's not that you don't want to let your colleagues know what's going on - just that any information you provide in poster format (or any other format) must be there in service of corralling together the right group of people with whom you want to talk.

What a poster is not about

It's a commonly held view that the purpose of an academic poster is to present information - which is how you end up with posters like this one below. We've all seen posters like this, which try to pack in as much detail as possible. In fact, they pack in an entire paper's worth of information. In theory, this should be a winning strategy: after all, when we write academic papers, we are supposed to go into detail - sometimes great detail. Careers are made on ultra-information dense papers.

Here's the thing though: a paper is not a poster. In poster-land, all of this information is only worth something if conference-goers are willing to stop, take a look, and hopefully chat with the poster creator. Unfortunately, posters like these though are much more likely to repel fellow conference-goers, even those people who might have been eager in other circumstances to have a conversation about the given topic.

Why does a poster like this make you want to run away? There are many reasons, but one of the biggest is that super dense posters like these require time to make sense of. And time is the one thing that people at academic gatherings don't have. There are no shortage of things to do at a conference and looking at your poster is in direct competition with: 1) looking at another poster, 2) going to a talk, 3) chatting with a colleague, 4) checking email, or 5) anything else. So, when faced with the prospect of spending significant time on a poster that may not lead anywhere, most people will opt to walk away.

What a poster is about (part one)

An academic poster should be a conversation starter. It should be a crowd gatherer. You need people to achieve your conference goals and your poster should be working overtime to draw those people in. At its best, your poster should be a facilitator for social experiences. Any information that you provide on the poster must be there solely in service of pulling people in.

So, how precisely do you use your poster to grab the attention of other conference-goers, so that they want to know more about your research? How do you get attention? Not with an overwhelming amount of detail.

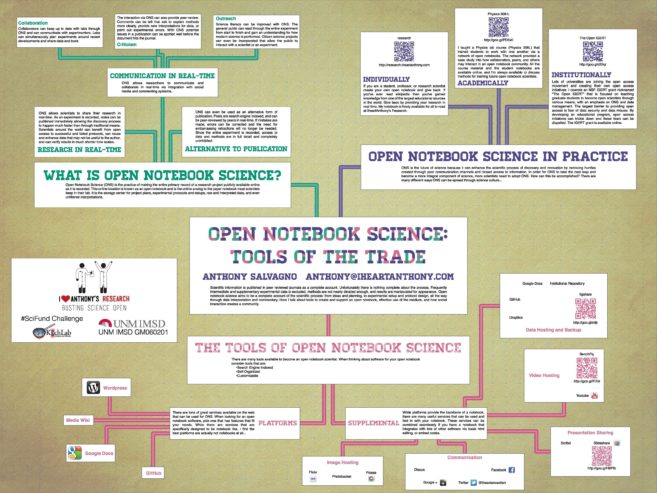

The right way to get attention with your poster is to clearly structure it around the one to few big picture ideas (preferrably one) that you want people to remember and that will get conversations started. Admittedly, there will be a portion of poster time when you are not standing at your poster. With this in mind, content wise, your poster should contain a complete story (without being overwhelming in detail). Take a look at the following poster, which provides an introduction to open science for scientists. The poster focuses on big picture ideas, with web links (and associated QR codes) provided in the poster, if readers want further information.

What a poster is about: helping you get what you want

As we've said, the main point of a successful poster is to facilitate conversations with people who can help you to achieve career goals. This of course begs the question: what kind of conversations would you like to have the poster facilitate? What kind of outcomes would you ultimately like to have occur because of those conversations? If we can start from the outcomes that you would like to achieve from your conference/academic gathering, we can then figure out how to design a poster to help get you there.

Before you start laying out your poster, it is essential to figure out how you want to use it to advance your scientific career. There are a three questions that you should consider in order to help focus your thinking. The answers to these questions will drive the content and layout of your poster.

First, what are the career goals you might have for a conference? Though there are many potential objectives, your goals may fall into the following categories:

- To improve your chances of getting into your desired graduate school programs by connecting with potential advisors.

- To improve your chances of getting a job by connecting with potential employers.

- To increase uptake in your field of a new method that you have created or improved upon.

- To increase the citation rate of your research papers and to improve the visibility of your research generally in your field.

- To find new collaborators.

Second, once you have identified your primary goals, the next question is: who precisely should you connect with at a conference to achieve those goals? The answer is most likely a very narrow set of people (most likely in your field) or perhaps even one person. Identifying the exact person or people who can help advance your career isn’t always easy and isn’t necessarily the first person/people that come to mind.

Last, what is the one-point message that you want your target audience to remember? Conferences are busy places and there always is an overload of information and events. As a consequence, you’ll want to keep your primary message very focused in order to increase the chances that it cuts through the clutter and actually registers with your key people. You can present a wealth of information and subpoints that support your main message, but that main message needs to stand up and stand out even if all of the details are forgotten.

Exercise 1: Your Message

Consider the answers to the following questions and write them down. The answers to each question should be no more than two sentences.

- What is the career goal that we want to achieve at your conference?

- What specific person or people do you need to connect with to achieve that goal?

- What is the focused message that you want your target person(s) to remember?

- One way to think of the last question is to imagine someone in your target audience has walked up to your poster, and asked, “What’s to learn here?” You should be able to provide your message in one or two sentences.

- How does this take away message advance your goal with your audience?